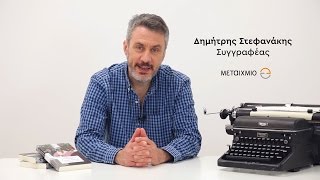

Στο Διεθνές Συνέδριο με τίτλο «Η Μεσόγειος ως χώρος μνήμης» που γίνεται στο Ηράκλειο Κρήτης ο Δημήτρης Στεφανάκης

Η συμμετοχή του Δημήτρη Στεφανάκη στο Διεθνές Συνέδριο με τίτλο "Η Μεσόγειος ως χώρος μνήμης" που γίνεται στο Ηράκλειο Κρήτης. Η επίσημη έναρξη του συνεδρίου συνέβη στη Βασιλική του Αγ. Μάρκου, την Δευτέρα 24 Απριλίου 2017.

It is often said that the Mediterranean world isn’t but a figment of Homer’s imagination in the sense that the great poet defined its narrative dimension through Odyssey. Indeed Ulysses is considered to be the first cosmopolitan. The king of Ithaca sets out on his quest when he gets desperately homesick. At the end of his epic adventure he thinks of the Mediterranean as his homeland - the same homeland that all of us share up to this day.

We generally state that past is silence and what makes that silence speak for itself is the magical voice of literature. With the help of fiction we bring back to life a considerable part of a long lost universe. It is amazing how people of old times led such a fascinating life, as if the human being constantly invented various episodes of a magnificent novel.

There are two ways of telling stories: either as a historian or as a novelist.

Both ways implicate the quality of memory that enables a person to recall any element of the past. Storytelling is a kind of war that humanity has declared against time and therefore degeneration. In that perspective memory ensures a bare minimum of immortality.

We think of History as a stage where kings, fools, murderers and tyrants parade in a Shakespearean way. In this grand domain everyday life is of little importance. Historians have the tendency to traverse past time in strides. Historical events are the official side of truth. There is nothing to be doubted in these monumental moments of time that we call History.

In my opinion, though, it is not a question of truth as historians usually claim, but rather an attempt of reinvention. In reality we reinvent what took place years or even centuries ago. Although it is not quite clear whether memory is a tool of storytelling or vice versa, the first has everything to do with time. We narrate what we are able to remember not only from personal experience but also from collective memory. In the Alexandrian Quartet by Laurence Durrell, for example, the author sheds light on the recent history of Alexandria with the use of multiple fictional characters. In doing so he manages to recap a point in time known as Mediterranean cosmopolitanism.

We often treasure memory considering it to be equivalent to accuracy forgetting that memory often becomes as partial as History can be. Literature lies somewhere in between them; seeking after its own truth succeeds in bringing out a direct experience of everyday life.

The present is the capital of time and it certainly is a dazzling one with technology and all. Although only temporary it is inevitably intertwined with reality. On the other hand, past has a captivating influence on modern era. Expelled from the kingdom of time people of the past keep on fascinating us with their magnificent creations. It is past time that feedbacks our aesthetic.

We are mortal: this is time’s deepest meaning in storytelling. Fiction shows us the past as well as the present moment in a mortal light; it is an art served by the indelibility of memory. If culture is to survive it will survive through that very memory used by storytellers. That’s why we are used to saying literature is the art of remembering. In a way, memory is the only thing that beats time and death. Perhaps civilization just signals this triumph.

German painter and sculptor Anselm Kiefer once said: “I believe above all that I wanted to build the palace of my memory, because my memory is my only homeland”. It seems that people develop a special bond with time as well as place. Artists in particular draw inspiration from past times. In that sense art is the genealogy of time, the same way that civilization is of human race.

After all, what else could memory be than a side effect of time? Both History and literature shape this memory, while keeping track of notable moments. In the sea of time these moments seem to be small islands inhabited by nostalgia. Nonetheless it is not because of nostalgia we are attracted to the past. We are right to consider past time as a tank containing vital information for our future. We are also right to call this tank human civilization.

Language has its own memory. Indeed, we use the word ache after having experienced pain. In the same way love, which is most poets’ favorite subject, traces in memory the most precious feelings. It is generally acknowledged that this word game is based on recalling a specific experience. If you try to think of a word detached from memory you will probably not succeed. This reminds us of Plato who claimed that knowledge isn’t but reminiscence. Either way we are in desperate need of memory so that we may be able to reconstruct the lost universe of the past. During this process literature and poetry in particular, seems to be a monument of words.

Perhaps we live in an age when great poetry can’t be written. It is possible to argue that today Homer and Virgil would have written in prose, that Shakespeare would have composed novels. This has to do with the indisputable fact that modern prose has become too poetic. One of the pillars of literature, the man who put full stop to this form of art, author Marcel Proust, gave us the perfect example of a prose flavored with poetry. In his autobiographical novel in Search of lost time the French novelist follows the narrator's recollections of childhood and experiences into adulthood during late 19th century to early 20th century aristocratic France. Most specifically he reflects on the loss of time while trying to regain the lost moments through memory. Proust absolutely realizes the magic link between memory and time, he laments the passing of time but he takes comfort in the existence of memory. Following his example we should try to regain the lost faces of culture through this magical quality thanks to which the human being reinvents so often and so easily his own past.

Octavio Paz, the great Mexican poet writes:

Between what I see and what I say,

between what I say and what I keep silent,

between what I keep silent and what I dream,

between what I dream and what I forget is poetry.

Let me paraphrase his verses in order to say:

Between what I forget and what I remember is literature.

Dimitris Stefanakis

Comments - Σχόλια