Aria, The World From The Beginning - Missing (αδημοσίευτο - αγγλικό)

ARIA, THE WORLD FROM THE BEGINNING

MISSING

Storytelling is a kind of consolation. It gives you the right to leave out the people or things that make you feel shame, doubt, regret. I don’t know whether Christopher Alby, sitting in the front seat chatting to the driver all the way to Lavrio, would have agreed with me. Archaeologists after all have their own way of perceiving the truth. We could have taken the train, but he insisted on using the British Embassy jeep. On the last leg of our journey, where the road climbs up a wooded hill and passes through a small village before going downhill again, as if it’s about to run into the sea, the little jeep went jolting wildly over the mud truck and looked likely to fall to pieces at any moment. Chris however seemed completely unfazed and went on chatting to his compatriot and ignoring me. Every time he turned his head I had the sense that I was seeing two different people. His left profile looked fresher and more youthful but at the same time harder. With his right cheek to view, his nose and chin were more evenly defined, but the years had visibly left their mark. I wondered whether his two faces were a reflection of his character. The tobacco pipe protruding from his lips gave him a birdlike aspect, a bird of prey, to be exact. And the whole impression was submerged in the shade of the straw hat that each of us wore to protect us from the pitiless sun.

When we arrived at Lavrio the caique had not yet come in. The sea appeared calm, though a gentle north wind had picked up and grew stronger as the sun rose further in the sky. For the time being we looked in vain for some coolness off the sea after the heat that had overwhelmed us inland at Mesogeia. We sat in a cafe, at the edge of the harbour, under a bamboo shade. The proprietor, a giant of a man with expressionless eyes, served up some unexpectedly good coffee. He had a towel draped over his right shoulder which he used to wipe down the tables and flick away the flies.

Chris offered me a cigarette. We smoked, exhaling thick clouds of smoke. It was strange thing: the Englishman always had a pipe in his mouth. His relationship with it verged on the sexual. He looked at it, bit it, stroked it and would often put his finger into the empty bowl. But when he wanted to smoke, he produced cigarettes from an elegant tobacco tin and put his pipe away.

Eventually he took off his jacket and rolled up his sleeves, revealing thin, but sinewy forearms. Then he went and stood at the end of the pier and skimmed a few stones across the water. He bent elegantly at the waist and and stayed for a while without moving, with his thumbs hooked into his braces, waiting for the stone to sink to the bottom after a few flips. The Greek police from the Department of Aliens, who had been following us all the time, had stopped in the shade a hundred metres off. They got out of their official car, not wearing their jackets, and then they too rolled up their sleeves. One of them even pulled out a white handkerchief and mopped his forehead and his neck. The other one produced a newspaper and pretended to read it, leaning against the bonnet of his car. What could all this be about?

The Englishman anyway treated it all as a joke. He gestured me to come over. I had no desire to stand in the sun and throw stones into the water. I spotted an old newspaper on a nearby table with a half-completed crossword and tried to finish it. I was racking my brains to remember the name of Odysseus’s swineherd. I called out to ask him and he answered “Eumaeus!”

And then he went on with his game by the sea. The elegant figure of a Londoner ever by my side. We had become inseparable. Who would have thought that I would leave my post at the Greek Embassy in London because of him, and follow him to Greece for a summer which for many was the last before a new great war? But the Greek Ambassador’s instructions had been clear: “Mr Mavroides, you will accompany Mr Christopher Alby to Greece. Mr Alby is an archaeologist whose distinguished colleague, Lord Jonathan Lorimer, has just been reported missing in our country. The Greek government has offered its sympathy to his family in their distress, as well as to the British academic community, and it intends to offer every possible assistance in elucidating the matter”.

From Lavrion we were going to cross over to Zia by caique to present ourselves that same evening at a party held by the British School of Archaeology.

“They’ll all be there” he said, knowingly, when he came back to my table. Perhaps my reaction didn’t satisfy him because he went on:

“It’s an important event, I tell you”.

“How important?” I enquired. “Will it help us to find the lord?”

“Probably not, but even you can’t be thinking about the lord all the time.”

“I thought that you were concerned about his fate?”

“Well naturally, but”-

“At the Greek Embassy in London you seemed to be genuinely worried”.

“But of course I am just as worried now”, he replied and momentarily twitched his lips as if he were searching with his tongue to remove a piece of food from between his teeth.

“No, but I was under the impression that you two were friends”.

“Of course we are, but we were also colleagues”.

“So what? The one doesn’t rule out the other”, I replied sharply.

He laughed, displaying a fine set of teeth. And then he swallowed hard and took on a more serious air, as if he were about to say something portentous.

“We are good friends, at least so I would like to think”.

“And is that why you undertook to track him down?”

“That too. Although I believe there is more at stake here than just friendship: The academic reputation of a great archaeologist who, in my view, is without rival. Your uncle would understand exactly what I mean.”

“I was under the impression that in his case what counts most is his aristocratic title and the influence of his family”.

“Ah, so you know! A marriage of convenience, that’s the truth of it. The title, the money. Jonathan never needs to work again. Nevertheless he was constantly escaping from his wife’s castle to indulge his passion for archaeology and beautiful women. But the fact is, he is irreplaceable. His excavations and publications about the Mycenean period will be epoch-making”.

“Did Uncle Hector ever work with him?”

“Naturally. How many years is it since you saw your uncle?”

“Quite a few. Not since we lived in Smyrna, before the catastrophe. And I was a child then”.

“But of course you were a child then, Stéfané”.

“He wrote to us frequently though”, I added, as if I wanted to justify him in some way.

“A good man”. He agreed.

“He was indeed!”

“It was a tragic loss. I could never understand what he and Susan were doing on that country road in Moreton”-. At that moment a whistle blast broke the silence of the summer morning. The caique for Zia was entering the harbour.

I now know what it means to return to the sunny mediterranean after the impenetrable gloom of the north. The previous thirteen years had rolled on to the melodious patter of London rain. Studies in law, and disappointed hopes of a career in my uncle’s shipping business, led to my finally settling on a career as a diplomat. I prepared myself for the winter entry exams to the Greek Foreign Ministry in 1932. The examination included a plethora of subjects - French, diplomatic history, English, consular, public and commercial law… I was meticulously prepared and I think I owe my success to the Greek Ambassador in London, who tested me before the exams and appeared to be pleased with my performance.

“Now that you’ve passed the tests I’ve set you, there’s absolutely nothing to be afraid of, Mavroides”, he told me.

He wished me luck, gave me a letter of recommendation and sent me to Greece for the exams. My success justified his faith in me. He engineered a three year interlude for me at the central office of the Foreign Ministry until I could get back to London. I remember as if it were now my first day at the Ministry. It was winter and the Minister received me in his office, smiling broadly under his military moustache.

“Bankers in Smyrna, shipowners in London, cotton merchants in Alexandria, and now, thanks to you, diplomats in Athens. There is no end to the glory of the Mavroides family!” he exclaimed, clasping me by the hand. He had invited me to come a quarter of an hour before the other successful applicants. An intimate friend of my uncle’s in London, that much I knew. What I did not know was that he saw, in me, himself as he had been at the beginning of his career. My performance in the examinations had impressed him and the examiners both.

“My esteemed teachers once spoke of me in just the same way, after my exams all those years ago. So I wish you as bright a future and, why not, maybe some day you will take my place. Greece has need of good men”.

Generous and polite, he knew how to preserve the formalities. When the others arrived, they would never have guessed that there was a family connection. Afterwards I was given a position in the political section for European affairs. In the beginning I was insufferably bored, copying out documents, but having said that, I learnt to decipher code. I was able very quickly to read the telegrams when they arrived in code from the various embassies. I never met the person whose job I took. He had left by the time I arrived. There weren’t enough people to do the work but there was also a lack of space, which meant that I had to share an office with my boss. The atmosphere was stifling. I could feel his eyes on me the whole time, I had no privacy whatsoever. How could anyone work like that? You were scarcely allowed to breath. And the way he addressed me “Mavroides my boy”, was to follow me reechoing through my dreams.

The work was more than I could cope with, but it was more the place and the people that stifled me. The compulsory suit. Its weave, its cut and its trimmings were all in some way indicative of your status - as was your bearing in general. Respect had to be shown even to the porter, who had rights due to length of service, but no-one respected me or my eight hour day. For the most part I missed lunch, and any private social engagements as well. I accepted the fact that I couldn’t plan anything. After a few months my mother ordered cloth and asked the tailor to measure me up for a diplomatic uniform and tricorn hat.

Uncle Daedalus from London bought and posted me the sword of a well known ambassador who had died. In the accompanying letter he wrote: “This sword bears a distinctive decoration on the handle, admired by George I of Greece. May it bring you luck, nephew!” Will I never be free of my family’s megalomania! From now on I must leave room in my suitcase for the uniform. How many times would I wear it in my life? Hardly at all. The flashy court dress with its gold laurel leaves, its crimson embroidery, its wide piping down the trousers, the tricorn hat, and above all the sword, cost a fortune and was destined more than anything for the grave, since they bury you with it.

You would have thought that daily contact with one’s colleagues would be a foundation for strong friendships. In reality it intensified the competition. In those three years I made one friend, but he left when he was posted to our Embassy in Vienna. Occasionally I received greetings cards with his name, Haris Abramides, and the designation of FRIEND. Soon even they stopped coming. It was he, as second secretary at the foreign office, who taught me that there is no such thing as a friend in the life of a diplomat. A controversial character and highly ambitious, he condescended to keep me company with the self-satisfied air of a teacher who wanted to initiate me into the ways of my betters. He took zealous pains to bring me closer to the spirit of the diplomatic service, and he was the first openly to refer to the subject of marriage.

“A diplomat, unmarried and childless..” he would say and frown disapprovingly. He himself, as far as I knew, never married.

My promotion to third secretary coincided with a transfer to the Embassy in London. It was thanks to the Ambassador, who had made a point of asking for me. I would be lying if I said I wasn’t happy. His intervention had helped me pick up the broken thread of my London life.

I simply had to wait until the British Foreign Office recognised me as a Greek diplomat and issued me with my papers. “You will be my right hand man”, declared the Ambassador on my first day at work. “I need a man who is calm and discreet, with an adequate knowledge of the law. What do you say, will you manage it?” He asked me.

“Certainly, Sir”, I barked, which made him chuckle approvingly.

Two weeks later, he was somewhat subdued when he received me in his office and I wondered whether I had erred in some way but he noticed and said “Don’t worry my boy. I haven’t called you in to rebuke you. I have to tell you that your uncle Hector and his wife have been killed in a car accident in Moreton..”

I bowed my head.

“Aren’t you going to ask me how it happened?”

“What difference would it make, your Excellency? I only hope we have not upset you”.

“Whatever do you mean my boy? We are talking about the death of a close relative..”

I was so grateful to him that I felt bad about troubling him with the death of my uncle. Only later did it occur to me that, after all, the tragic event was neither my fault nor Hector’s.

He could at least be left with the impression that Sue was Hector’s lawful wife. I let him think so.

My uncles in London, who for years had been whispering behind Hector’s back, nevertheless allowed him to be buried in the family vault with his companion, in the Greek Orthodox cemetery in West Norwood. On that unforgettable day I found myself in a sea of tweed - the British archaeological fraternity were there in force to honour their distinguished member. The epicedium was given by Admiral Barry Domvile, who spoke about Hector's personality and their work together with the generosity of a man who held a great affection for both. His bantering tone scoffed at Death and fate and it seemed to me more genuine than the mournful and reserved expressions of the others who, after the service, all squeezed their way into the Caxton Bar of St Ermin’s Hotel, near St James’s Park, to have a drink in memory of the couple. Many of them pressed my hand and expressed their condolences. I can hardly remember a name.

I let a few days go by and then went to the cemetery on my own with an armful of flowers which I laid on the plinth of the Mavroides family tomb. Afterwards I decided to take a walk in the park. It was a sunny Sunday in September, the Ambassador had told me that he wouldn’t be needing me, and the gentle sunshine made me feel as if I had all the time in the world. I remember that I was approached beneath the plane trees by a strange man, who didn’t mince his words. In a whisper, he said:

“Your uncle, sir, was the victim of a cold blooded murder”.

I turned and asked him abruptly: “And how would you know that?”

“I know it. Are you not interested in finding out?”

“No!”

Maybe I spoke like that because I was startled. After all, I wasn’t likely to trust a person appearing out of the blue. But I thought of it often afterwards. Why would he say that to me?

The plot thickened when ten days later a small box was delivered to me. Inside I found the number of a deposit box at the central London post office, along with a key. The next day I went to open it and found that it contained a parcel tied with string. Intriguingly the parcel contained a number of blue folders and some letters.The letters bore the names of people well known in the arts, expressing their pro-German sympathies. What did my uncle have to do with them?

As for the folders, I studied them whenever I found the time, which wasn't easy during that period. I worked out that they were all connected with the death of Lawrence of Arabia. Until then I wasn’t aware that they had known each other. Not only did they know each other, but it appeared that my uncle had been carefully researching into the cause of Lawrence’s death. From the folders it looked as if he had been collecting information with the intention of writing a novel based on his life.

To tell the truth, at the end of 1935, I had, or thought I had, more pressing problems on my mind. I was at the start of a career which I had imagined would be different, and the strict environment of the diplomatic service gave me the feeling when I woke up every morning that the world had suddenly been transformed into a vast army camp. From time to time of course I pondered the mystery - the messenger’s identity, the reason the package came to me, the people involved in this affair. The abdication of Edward from the throne of England in December of ’36, for example, startled me. His name had been frequently referred to in Hector’s folders, linked to efforts to bring about a rapprochement between Britain and Germany. His romance with the American divorcee looked like something from a fairytale. But hidden behind his declarations of devotion to that woman lay the pressing need for him to abdicate because of his pro-German sympathies.

It seems that the whole business was preoccupying me much more than I wanted to believe, to judge from the fleeting dream I saw practically every night: my uncle’s name written in English (Hector), on the sand, and then being washed away by the waves. If the writing symbolised my duty to his memory, then the sea represented the daily London routine that unceasingly distracted me from it.

This daily routine began in a furnished two room apartment in leafy Hampstead, where I had moved as soon as I took up my post. The house belonged to an aged spinster, and every time I met her she held a novel by Jane Austen or George Eliot clutched under her arm as piously as if it were a bible. I never once saw the woman who cleaned the house, but she left behind her an odour of beer and bacon mingled with cigarette smoke. I loved that flat, even though it couldn’t compare with Uncle Daedalus’ villa, a few blocks further down, where I had been living until then. It was a convenient solution for me, since I didn’t want to burden my relatives any further, nor did I want to live at the embassy. We worked quite hard enough there all week.

Our working day was usually more than eight hours long and even Sunday was not considered a holiday, which meant that if there was work to be done we had to be back at the embassy straight after church. The worst moment of the day was always when I copied out the week’s telegrams for the archive. I always thought it a bit unfair on the part of the Ambassador, even though I knew it couldn’t be otherwise. Perhaps because I had once seen a colleague copying them out while standing up, as if it were some kind of punishment. It was this kind of thing, over time, that turned my gratitude towards my superior into a growing sense of resentment. I have to admit that for the first three years I found it impossible to adjust to my new situation. But just when I was beginning to get used to it the Ambassador called me into his office one morning, in the presence of Christopher Alby, to inform me that I was being sent to Greece.

“I had hoped that I would at least be able to complete my four year term with you, Mr Ambassador” I said to him once we were alone.

“I too, my boy, I too. However in a few months you would have been leaving in any case. And this is an important, I should say an extremely important, affair. The king himself is passionately concerned about the fate of this missing person. Do your best, your very best!”

He showed me the photograph of the man we were looking for and I only muttered:

“That’s him then!”

“That’s him!”

I really felt that the whole business was rather tiresome.

It meant that I had to leave my rented flat in Hampstead as soon as possible and gather up my few possessions, mainly clothes and books, into two suitcases. Luckily there was plenty of space available for my diplomatic outfit. On the afternoon of the same day I went back for the first time in a while to the Caxton Bar for a meeting. The man was obliged to come up to me himself before I recognised him. He seemed surprised:

“Really, don’t you remember me? We met in the autumn of 1935 under the plane trees in St James’s Park”.

“It was you, was it?” I remarked suspiciously.

He bore no resemblance to the irksome stranger who had spoken to me then. It appears that sometimes the impression one gains of a person has more to do with one’s own emotional state than their actual appearance.

“Are you going to talk about my uncle again?”

“Why are you so aggressive with me?”

I noticed a slight trembling of the hand, a sign of nervousness which gratified me.

“I am not being aggressive. I am trying to understand what you want from me”, I continued in the same tone of voice.

“Your manner, I have to admit, makes my job much more difficult.”

“And what is your job?”

“For a start you have greetings from Joseph Ball”.

“Thank you but I have absolutely no knowledge of the gentleman.”

“It doesn’t matter, he knows you very well. You must have noticed that we have been following you for some time now. With the best of intentions, obviously.”

When he finished speaking he chewed his reddish moustache and looked at me, waiting to see my reaction. He hid his right hand under the table. He didn’t want me to notice that his tremor had increased.

“Who are you people and why are you following me?” I asked him calmly.

“That doesn’t matter so very much. In any case, you’ll find out soon enough. The point is that we are concerned about you.”

“For what reason?”

“You are Hector’s nephew. That is reason enough, believe me.”

“I don’t know what you are talking about. I am leaving for Greece in a few days.”

“We are aware of that, Mr Mavroides, just as we are aware of the reason for your going”, he told me, pronouncing my name in English with some difficulty.

“I’m not surprised. Is there anything that you are not aware of?”

“No-one is aware of everything”, he commented. That is why we must help one another”.

“What’s in it for me?” I asked, and was immediately ashamed of my cynicism. He smiled and said:

“Maybe we will find out who killed Hector”

“You are determined then, that it was murder?”

“In cold blood.”

“That’s the same expression you used in the park.”

“Really? I don’t remember. Maybe..”

“And why are you so sure? I mean to say, the official report refers to a car accident -”

“Well, then..” he remarked, with a touch of irritation.

“What can I say? I am amazed!”

“You must be aware that it is all linked”

“All?”

“The death of Lawrence and Hector, the disappearance of Lord Lorimer..”

At that moment it occurred to me that we had not once mentioned aunt Sue, and that it wasn’t fair of us.

“I don’t see how they are connected”, I insisted.

“And yet, and yet…” he murmured and started frantically searching his pockets. “I’m afraid I’ve left my cigarettes at the office”, he said.

I took mine out and offered him one. I gave him a light. We smoked together and remained silent for a while, solemnly musing on death.

Then he spoke to me about my uncle and told me the things I had already read about in the blue folders. He seemed completely unaware of their existence. Strange! Then he referred to the archaeologist who had gone missing. If I had let him, he would have gone on talking to me till morning. It was growing dark and I invented a previous engagement of some kind to get rid of him. We left the bar of the St Ermin’s and as we parted, he shook my hand and said simply:

“Joseph Ball thanks you for agreeing to see me today”.

I shrugged my shoulders nonchalantly and left. I turned for an instant to memorise his appearance. He was still standing in the entrance to the hotel watching me. He was my height, but very slim, and he wore a wide, ill-fitting jacket. It occurred to me then that he hadn’t even told me his name.

Whenever I have watched a shoreline receding, any shore, I’ve felt as if I am leaving behind a part of my life that I would never get back. In 1919 I watched as the shore of Asia Minor disappeared over the horizon. Twenty years later I was leaving a harbour in Attica, with two policemen watching us from the jetty, their eyes dazzled by the summer sun.

The caique chugged its way out into the open sea, and once we passed Makronisos, it began to toss about in the rolling waves like a walnut shell. The captain was a short thickset man called Petros. His eyes appeared to have taken on the colour of the sea. He wore a sailor’s cap which he nervously adjusted back and forth on his head. Every so often he would turn round and look at us each in turn as if he were repeatedly taking stock. Maybe he was genuinely surprised that ten people had entrusted themselves to his small unsteady craft.

Among the passengers there were a young couple together with an older woman. They were going back to their island and appeared to be exceptionally joyful. The grandmother had a small basket between her feet with two live birds. Every so often they would ruffle their feathers and squawk, and the young couple would smile at me apologetically. For my part I observed that Chris was biting his pipe pertinaciously in an attempt to fight away a slight sense of sea-sickness. We were standing in the middle of the boat, because the waves were spraying up over the side and our suits would have been drenched. We held our straw hats to stop them being carried off by the wind. The noise of the engine and the splashing of the waves drowned every sound and you had to shout with all your might to be heard. So we all preferred to remain silent and absorbed in our own thoughts. Only the old lady every so often spoke to the young couple in a voice like the squawking of the chickens. Old people can’t abide silence, and chatting is a way of forgetting death.

When after three and a half hours we at last arrived at the port of Zia, with the lighthouse towering above to our left, the ceaseless throbbing of the engine stopped and the caique gently glided towards its anchorage, as if it were being stealthily pushed to the pier by an invisible hand. The memory of a not particularly pleasant journey had already been cast into the sea like excess ballast. It appeared that Petros considered the arrival of his boat on the island to be an event of some importance, otherwise he wouldn’t have made such a rigmarole of making fast to the quay. Two locals ran to help him, and a there was barrage of cursing. For a person not familiar with the braggadocio of seamen, from simple fishermen to ship’s captains, it would be hard to credit the upheaval involved. Suddenly a crowd of people were gathered on the quay. Some helped the passengers to disembark, some stood by to take the luggage, others just looked on.

Among them stood Martha Graham, the secretary of the British Archaeological School who was there to welcome us, along with an employee from the Municipality. She had a good figure, but nothing to write home about: a redhead, with freckles on her face and small brown eyes that grew wider when she smiled. She wore a wide brimmed hat beneath which her body seemed to be cowering to keep away the midday sun. After greeting us with a few phrases in broken Greek, muddling the genders and the verb endings, she reverted to her mother tongue. Chris asked her if she was still taking Greek lessons and she admitted that she had in fact given them up. Beside her, the man from the Municipality, with the kind of forced politeness that makes you feel awkward just because it is so obviously fake, attempted to take my bag. I indicated that it wasn’t necessary but he insisted.

I couldn’t see any reason to disappoint him, especially when he said: “I’ve heard that you are a diplomat. My warmest congratulations!”

Disingenuous admiration flashed through his glance. I imagined that perhaps he had once dreamt of such a future for himself. If he had asked me, I would have assured him that the job of a diplomatic servant isn’t all that remarkable, especially for the first few years. Just in front of us I noticed a line of mules waiting for a fare. One of them was stamping its front right hoof repeatedly on the paving. Its owner was trying unsuccessfully to calm it. Chris wanted us to hire a beast of burden, but the others laughed, and Martha said that our lodgings were only a hundred yards from where we stood. A small settlement spread out like an amphitheatre onto the hill above the port, the houses like sea birds nesting in the rocks and their tiled roofs like birds’ crests. If we were going to be staying in one of the last ones high up there it might not be such a bad idea to go by mule. But luckily we were destined for a two-storied house along the sea front.

From the balcony you could see the uncultivated barren landscape opposite, alleviated by a little chapel and behind it the stone villa Alifrangki, or “Villa of Mistrust”, surrounded by thick pine woods, its fence a number of white posts climbing up the grey green rock. It immediately brought to mind the years in Smyrna and the family villa in Boutsa. The two buildings might not have much in common from the outside, but there were bound to be many similarities hidden inside. Cosmopolitanism throughout the Mediterranean was characterised by the same obsessions.

Those were my thoughts when Martha came back with the man from the municipality and they took us out to eat at a little taverna a few metres further down. We were three tables in all. At one a party of fishermen were sitting and getting drunk. It’s incredible what you overhear from a party of drunken men. If you took what they said seriously, you would have thought that you were listening to heroes lifted from the pages of Homer’s Iliad. It seems that the glory of the race travels on from generation to generation through tales told in cafes and tavernas, consisting of obvious fantasies which are invented not to convince anyone, but simply to pass the time.

We had hardly managed to sit down before a carafe of wine arrived, along with bread, salad and a plate of fried fish. The man from the council, whom our neighbouring fishermen called “Antonaki”, offered to pay for our dinner. Antonakis apparently considered it a great honour to be having dinner with us, and looked as if at any moment he might apologise for the peasants who were spoiling our peace.

There followed a siesta. Except that when I lay down I realised that my dizziness was due not so much to the wine as to the rocking of the caique. The heat complicated things further. In the end I fell asleep with the sensation that I was still on board. I woke to the sound of repeated knocking.

It was Chris calling me: “Wake up wake up lazy bones!” The light now fell softly and dimly through the shutters of the balcony door; evidently I had been asleep for several hours. I answered him in a voice which even I hardly recognized. In under a quarter of an hour I was ready and knocked on the door of his room. He opened it and I found him carefully combing his slicked back hair, giving to the whole procedure a rhythmical flourish. I had never before seen such a full head of hair on a person. His scalp was amass with fiery blond hair hanging low over his brow. Once he had subdued the sheer volume of it with liberal doses of brill cream, his thick locks looked sleek and kempt.

As we left I saw why we had to hurry. The light like an eyelid slowly closing was fading with the sun as it slipped behind the hill. The days in late July are long, but this one had been wasted in a reviving sleep of several hours. Chris, by contrast, had not slept for one second. At least so he said, despite the fact that he had a freshness about him only achievable in the arms of Morpheus. At the end of the wharf a very different Martha stood waiting. In an iridescent and flattering dress, she had managed to look almost beautiful. Chris compensated her efforts with a compliment, which she accepted and tried to return, saying “What could I do? Since I was accompanying two such handsome men this evening, I had to dress accordingly”.

“There’s no need for that Martha. In any case beauty is nothing to be shy about”, he replied.

We walked on towards the villa following the road along the sea front, beside a long beach. The Englishman had been to the island a few years before to take part in the excavations on the peninsula of Agia Eirini, which he had pointed out to me when we were coming into the harbour that afternoon. It was at the far end of the wide bay. Lord Lorimer had been digging in the same area.

Half way there we came upon some dozen locals with grubby hands and faces, as if they had been through smoke. They turned and looked at us strangely. Poverty and wretchedness were written all over them. A young man shot me a look of protest. His expression shocked me. Since childhood I had seen the poverty that passed before me as something natural and inevitable. In the poor quarters of Smyrna, Greeks, Armenians, Jews and Turks were gathered together in a squalor which seemed to us merely picturesque. I never asked myself why it was necessary for these people to live without all the things that the aristocracy enjoyed in abundance. And strangely it took the persistent look of that unknown man to put the question in such a dramatic way after all these years.

Chris explained to me that they were probably workmen loading coal for the ships from the wharf opposite. “They get up at dawn and set off on foot from the other side of the island, walking over the mountains in order to come and work down there for sixpence halfpenny. Until the sun goes down. Then they set off back home again, exhausted and covered in smut, as you see”.

“And what kind of a life do you call that?” I burst out rather suddenly.

He didn’t answer me. He shrugged his shoulders.

Martha paid no attention to the incident. She was most probably thinking about the impression her outfit was likely to make at the British School. At some point she asked Chris a question but he made no reply.

“Martha is asking you a question” I shouted, but he still pretended not to hear.

I did not approve of his behaviour towards her, and she noticed and began making signs to me behind his back, which I liked even less.

At the turn in the road we saw the villa before us, as if lying in wait there in the twilight. The spare, stone building perched on the ridge of a hill looking in vain for shelter from the north wind under its tiled roof. Pines encircled it like sleepless sentinels. A sturdy wall marked its boundary and its wrought iron gate stood wide to welcome in the guests.

We were greeted on arrival by a colleague of Martha’s. They spoke together and afterwards she introduced him to us. Chris behaved as if he couldn’t care less. He practically pushed his way past the man and a smile lit up his face only when he saw the Director approaching, Jerry Young, accompanied by the owner of the Villa. Once again I felt embarrassed by his behaviour. “Who does he think he is?” I said to myself, smiled at the underling, and exchanged a few words with him. Then I heard the British archaeologist saying to me.

“Come on Stéfané. What are you doing? Come and let me introduce you to our hosts”.

I was forced to abandon the snubbed assistant. I hate it when people are rude. On the other hand, this person was not suffering as much as the locals I had met a little earlier, which was a comforting thought.

I let Chris introduce me and he did so emphasising my diplomatic status. Which meant that I was able if only momentarily to engage the attention of the two people who were our hosts for the evening.

“Where are you from Mr Mavroides?” Alifrangkis asked me.

“I’ll tell you who he is - he is the nephew of Hector Mavroides, a distinguished English archaeologist who worked with us for years”, interjected the British director. The strange thing was that although our Greek host spoke to me in English, out of deference to his guests, the director and Chris seemed to find it natural to speak in Greek, since they were in Greece. “I believe that your family come from Smyrna, correct me if I’m wrong”, he interjected, and smiled at me.

“You come from the great Mavroides family. Banks in Smyrna, cotton in Alexandria, ships in London”, remarked Alifrangkis and I caught in his glance a flash of the trading zeal characteristic of our race.

“That’s right.”

At all such gatherings it is the custom of distinguished people to dispense amiability to all and sundry, which to someone not accustomed to it might seem surprising. But I had been to many such occasions throughout my childhood and I was familiar with the rules of the game, so I was not put out when two seconds later they moved on and paid me no further notice. Just as I would not have been surprised if after one or two hours they were to rediscover me and begin all over again to be effusively polite to me. Just as I never thought it worth mentioning how swiftly day turns to night on a summer sky over the Aegean, where in the dark blue dome of the universe numerous stars suddenly make their appearance.

It was a warm moonlit night beside the sleepy sea, its calm broken now and then by the voices of the British revellers. The men wandered about in their light linen suits like so many cheerful ghosts. The ladies were making the most of all their summer dresses and noisily showing off their colourful get ups. In the end there was quite a gathering. The orchestra, positioned in full view, played lively pieces and attempted from early on to inspire in us an impulse to dance. I noticed that the musicians, dressed in white, were going to considerable efforts to make themselves heard above the din. Their striving was evident in their exaggerated facial expressions.

In any event the evening was not to be a staid intellectual gathering. The archaeologists had come there to have fun. For the time being people concentrated on getting to know each other. Some stood on the edge of the sea looking out towards the moon which was almost full, the resplendent glory of the evening. It’s light sketched out the unlit harbour opposite. Martha, impeccably polite as always, did not want to leave me alone, but I realised that it wouldn’t do for her to stay beside me all evening. So I released her from my presence, and she appeared to be relieved, as was I. As for Chris, when he was with the English he became an Englishman and acquired the snobbery of the empire. He had almost forgotten my existence, and if I had reminded him of it I am certain that he would have turned to me with the expression of a person who is being inconvenienced by a stranger. For one instant only he concerned himself with my person, and then only to say:

“Do you know that man?”

“No.”

“It’s Ellis Waterhouse”.

“So what?”

“Important man”.

“I have no doubt, but why?”

“He works as a cartographer at our Embassy in Athens”.

“And why should a cartographer be so important?” I asked.

“Don’t jump to conclusions. He happens to be a brilliant historian and art critic. You should look at his work on El Greco. A superb achievement. He was made a fellow of Magdalen College Oxford last year”.

“Ah, indeed”.

“That was my uncle’s college”.

“I know, that’s why I mentioned it”.

“And what is a brilliant art critic doing in Greece working as a cartographer?

“That’s no business of yours”, he said, leaving me speechless.

Art critics had invariably provoked in me an irrational fear, in the same way as judges did. I must have been scarred by the terror that my father felt, as a painter, when faced with famous critics. He would often describe them as an unapproachable sanctuary that arbitrated over the holy inspiration of the artist. The tyranny of their criticism put the dampers on the artistic urge. “Will that blessed day ever come when we shall be free of them?” said Angelos again and again, predicting a revolution that would change the world. As I grew older I came to the conclusion, among other things, that my father was a mediocre painter. I never said anything to him, because I realised from early on that the fantasy of his greatness was the corner stone and foundation of our family. Oraia’s unstinting admiration of his paintings was what had nurtured her devotion to him all those years.

Hector once dared to make an ambiguous remark about his brother’s work, thereby unalterably poisoning their relationship. I believe that my father ended his days tortured by self-doubt.

I imagine that if he had been in my position he would have approached the famous art critic with conflicting emotions. On the one hand, he would have been eager to show him his works and pass muster. On the other hand, nauseated by the arrogance of the critics, or what he imagined to be arrogance, he would have walked on by with a supercilious expression.

For my part, since I did not depend on his judgement, I simply observed him. Tall, bespectacled, he seemed to move without a centre of gravity, and appeared engagingly clumsy. I studied his eyes, eyes that could pierce through the multiple layerings of artistic creativity to find its marrow. Contrary to what Angelos maintained, there were some enlightened critics but they were few, just as there were few great artists. Nowadays I knew this for a fact, and it was confirmed by what I saw in Ellis’s eyes, as he gazed about him with an air of reserve.

We were living through changing times, and people were taking up unexpected roles in support of an idea. If you were to ask them, each would give a name to his idea - country, humanity, civilization, international justice, the future of his children. Waterhouse was almost certainly envisaging his own ark in which, if necessary, he would save a few important works of art. For him the great fatherland of art was equally endangered by the savagery of an ideology. It was time to face up to it, not in abstract theoretical terms, but with both feet firmly on the ground.

Meanwhile the orchestra had moved from waltzes and polkas to playing the Charleston, Swing and Black Bottom. Couples who had been dancing on the terrace separated. Men and women stood opposite each other, and free of the tyranny of the dance steps they improvised with their whole bodies. Now the primal sexuality of it all momentarily overcame Waterhouse. He allowed himself to be led without resisting to the middle of the dance floor by a small but attractive Englishwoman, in a trial which for him must have been worse than war. People whose profession it is to judge others do not enjoy becoming the object of criticism themselves.

He overcame his instinctive reluctance and began to sway gracelessly . His body language made it clearly evident that Waterhouse was suffering. Watching him it occurred to me for the first time that being tall is not an advantage when dancing. He was sweating profusely beneath his white silk shirt and every so often he would pretend to hitch up his wide grey trousers just to give himself a break. His companion, by contrast, was enjoying to the full her dancing clothes, dressed as she was in a blue frock the colour of the sky just before dusk. I was certain that her joy would not last long. At the first opportunity her companion would make his getaway.

“Dear Ellis. He would get on fine with Helen if only he loved archaeology and dancing the teeniest bit”, commented Chris indicating the very end of his index finger with his thumb.

I didn’t see what happened next. Jerry Young came up and engaged me in conversation. Sometimes people end up staying single just because everyone thinks they’re bound to be snapped up.

“I knew your uncle well”, he said to me. He was holding a glass of champagne and swirling it about to release the bubbles.

“My uncle knew a lot of people”, I commented.

He obviously wasn’t expecting that response and probably took it to be rudeness on my part. I saw him blush and his moustache went up as his lip twitched momentarily.

“In any case, he was particularly beloved by us in Britain”.

“Our family, you should know, considers Britain to be a second homeland. I have two uncles in London who have worked in shipping for years and I myself have lived more in England than in Greece over the past 10 years”. I tried to appear more gracious.

“But of course, I have found out all about you, rest assured”. It was his turn now to feel awkward for giving the impression that he had been spying on me.

“I have no doubt”. I said to him, causing him to nibble his moustache.

“It is very noble of you to help us over the disappearance of Lord Lorimer. A notable archaeologist, and a close friend of your uncle.

“That I know too”.

“We had entrusted him with the excavation at Mycenae this summer. A matter of vital importance for the School. He was to have collaborated with a professor who will be coming from England in the next few days”.

“Have you no idea at all where he might be?” The director of the British School ignored my question and turned towards the owner of the villa who had appeared beside us.

“My dear friend, at last. I have been looking everywhere for you”, he exclaimed and clinked his glass. He took him by the arm and they moved away. In the meantime there had been developments on the Thomas - Waterhouse front to which Chris drew my attention by digging me in the ribs.

“Look at them. They’ve been spoiling for a fight all evening. I smell a quarrel in the air”.

I turned to where they had been dancing together earlier but I couldn’t see them. They had moved away in the interim to a corner of the garden; not only that but it appeared that Ellis had removed his spectacles and rolled up his sleeves, very much as if he were proposing to start a fight with her.

“Definitely a quarrel”, repeated Chris “Now watch what happens!”

What we saw was in effect a pantomime. With all the riot going on it was difficult to make out even the words of the person standing next to you, much less two people standing several feet away and who had no desire to be overheard by all and sundry.

“I guess it happens fairly frequently”, I said.

“Yes, how did you know?” asked Chris.

“I see that no one else is taking much notice of them, which means they must be used to it.”

“You’re no fool, Stéfané.”

“And what’s it all about?”

“I told you: Ellis detests dancing and archaeology. Particularly the latter. And no archaeologist in the world would forgive that”.

“A strange tribe you are”, I remarked.

“Most probably”, he agreed.

By the time I had turned back to look at them the couple had vanished into the night.

So long as I was observing Waterhouse I had something to do. The moment I lost sight of him I was left high and dry. I tried to join in one or two conversations without success. I even tried looking for Martha Graham, but I saw that she was talking to someone over in a corner and so I left her in peace. Then I fell to looking about me. There were a few people who had from early on taken possession of the parapet at the end of the rocks, and stubbornly refused to give up their prime position. Their laughter and voices jarred out of key in the gaps between the music of the orchestra. They didn’t mind being far from the heart of the evening and beyond the light cast abroad by the oil lamps. Under the moonlight now and then their hands slid stealthily over one another’s bodies. Equally fortunate were those who stood out on the little balconies above the ground floor with a view of the ocean. They had climbed earlier up the few marble steps to the formal entrance and passed through the two drawing rooms which led to the right and left onto cool little balconies. As I headed towards the downstairs loos I glanced into the inner rooms with their high ceilings. The spareness of the furniture was not necessarily a sign of penury, as might be imagined by some ignoramus. Maybe the owner was simply staying true to the local Cycladic style. To get from the hall to the kitchen you had to cross a narrow passage. First on the left was the small lavvy and after it the door heading to the cellar. Just as I was going into the lavatory I saw someone coming up the stairs laden with supplies. When I went back in to the party I noticed that a small group had gathered in one of the two drawing-rooms. Our host was explaining to the School’s director and two or three others the architectural concept of the house. I immediately sought refuge in the cool of the garden.

As the waiters went past I stretched out my hand without thinking and downed one glass of wine after another. Gradually and without knowing it I had ceased to be sober. Disaster finally struck when she appeared before me.

It’s a strange thing, reputation. Sometimes you would think that people were made up of words rather than flesh and bones. Stories built upon half-truths, innuendos and the unfinished sentences of others. So that you know them well, or you think you know them, before you’ve even met them, up to the point where you’re almost in love with the reputation. Chris had described the controversial atmosphere surrounding the British School in a manner befitting the opening of a great novel with its cast of heroes. Of all the things he mentioned I retained two figures. The vanished man and his young former lover. First and foremost I was attracted by her name: Rosemary Leblanc. A name such as that would indisputably confirm even the wildest surmise.

Chris put it to me bluntly:

“She is beautiful, my friend”.

“How beautiful, really, this much… or this?” I asked widening the distance accordingly between my hands.

He laughed, I remember and said to me “Is that how you measure beauty? Beautiful, I tell you, very beautiful. You’ve never seen such beauty.”

He didn’t know that he was speaking to the son of a beautiful woman. It wasn’t by chance that in Smyrna my mother was not called Panoraia, but simply Oraia - beautiful.

“So what?” I insisted.

“Let me explain it to you so you get it. This woman is not for the likes of us”.

“What? Oh come on!”

He shouldn’t have said that to me. I know myself well. If I think there’s something that’s beyond me, then that is the thing I must have.

Chris insisted, inadvertently complicating things further.

“Be careful. Keep far away from Miss Leblanc. And if you do happen to meet, avoid looking into her eyes, don’t pay any attention to her smile and if you want to take a look at her, do it very quickly like this” and he showed me how with the swiftest up and down movement of his head. It was my turn to laugh. I couldn’t tell if he was serious or not.

“You’re laughing? You may laugh! Let me tell you: four years ago a famous archaeologist climbed up on the acropolis of Athens in the full moon and cried out “Rosemary! Rosemary!”

“Yes but Lord Lorimer… he didn’t exactly have a bad time with her”.

“Lord Lorimer? I don’t know whether he had a good time or not. He was such a wreck every time the wee thing left him. They broke up for good last summer and I bet you he hasn’t got over her yet”.

“Ok Chris, I’ll bear it in mind!”

Beauty always takes us by surprise, because we cannot conceive it in all its various forms. Whenever I was attracted to a woman it was always because I had never imagined that such a creature could exist. Rosemary Leblanc, from the moment I met her, radically altered my view of the classic Englishwoman.

“Anglo-French”, Chris informed me, and maybe that explained it. I followed her movements as she pinned down the men, describing elegant circles with the cigarette she was holding. Exactly as the Englishman had described her to me: “A caryatid, with blond her and wide green eyes”. A tall woman, in truth. I wondered whether she was taller than me. When I went up to her, she pressed her shoulder against mine to compare our heights.

“I’m taller than you”, she said, the way one child might have said to another. Luckily she wasn’t.

Her smile brought a tiny dimple to her cheek, of the kind one yearns to kiss. Her lips had an unusual curve to them, but they suited her eyes, and the shape of her face. Dressed in a white evening frock made of silk, she had the air of a diva about her. Beautiful without any doubt, but after hearing so much about her I couldn’t judge objectively. A child of divorced parents, which I always found fascinating, as I did all people of joint nationality: French father, British mother.

After leaving Cambridge, she had taken part in archaeological digs for the last half-decade, but in the British community of Athens she was known as the woman who had “swallowed up” Jonathan Lorimer. Some said that it was he who brought her to Greece. Chris explained to me that their relationship was common knowledge to everyone except his wife.

Her Ladyship would not at all have liked the idea of sharing her Lordship with this striking beauty who looked men directly in the eye showing her defiance of the stronger sex. When we were introduced, she couldn’t be bothered to take in my name. She merely asked Me: “Are you Chris’s Greek friend?”

I didn’t like the way she put it so I turned it round, saying: “He is my friend”.

She didn’t hear what I said. She was more interested in the orchestra which was playing slow jazz. She tilted her head sweetly and pulled me briefly onto the dance floor to try me out as a dance partner, and then left me almost immediately. She held out her cigarette, I searched in my pocket hurriedly for a lighter, she brought my hand up to her cigarette, lit it, and inhaled deeply. Then she blew the smoke out into my face and went away laughing.

We were all destined afterwards to remember the party at the villa in Zia, after the carefree days of peace had long gone. Each of us had a reason to remember it. Ellis Waterhouse because he had lost Helen and was searching for her all evening. The police were called. Dressed in their summer uniforms - peaked hat, pale blue shirts with stripes down to the elbow, breeches tucked into boots laced up to the knee. The officer who took charge of the affair did his best in adequate English to calm the famous art critic and less famous cartographer, who insisted that he could speak the local language perfectly well. The Englishman was sweating anxiously, but he managed to make a joke of it, holding a compass with which he assured us that he would find his beloved. The Greek policeman indicated that I should follow him. He seemed to be an intelligent man and had a genial and sound look about him. He asked me under his breath.

“Tell me, is he quite right in the head?”

“No, officer. It’s just that he has an exaggerated sense of humour”, I assured him.

“I wondered!”

I imagine that he would remember the occurrence, since apart from anything else he was congratulated by the director for his knowledge of English. The owner of the villa confirmed to us that he was well thought of on the island. When the policeman found the lost woman hiding down by the rocks, I said to Chris:

“Do you think we should put the policeman in charge of finding Jonathan?”

He smiled and didn’t say anything. He in turn would remember the party for his own reasons. To tell the truth, I don’t know where he slept that night. At any rate he appeared back in his room at midday on the following day.

To start with he went off with a group of people who had paid the band to keep the party going on the beach. Musicians and revellers together stepped out over the pebbles and the sand to the sound of a somewhat weary and out of tune band. The wind instruments shone in the moonlight like the barrels of a gun. Later on, some people climbed into boats and spread out across the bay with their lighted flares making a grand display. I don’t know whether he went with them or whether he had picked up some girl or other. The next day I woke with a fearsome headache and went and knocked on Martha’s door in search of a painkiller. She popped her little face, still half asleep, round the door, carefully concealing the lower half of her body from view. I explained what I wanted, she asked me to wait. She shut the door and when she opened it again she put out her right hand only. In her open palm there was a small pill. I took it and thanked her, and went back to my room.

Towards mid-day I called on Chris. He opened the door wide and asked me to come in. As I did so I noticed his clothes neatly folded on the chair, an ashtray with cigarette stubs on the dresser, and three carefully chosen books on the floor. Homer in the Oxford edition, the poems of Yeats and a detective novel. He himself was shaving slowly, extending his right arm just exactly as if he were drawing a violin bow over its strings.

“Three books simultaneously!” I remarked.

“I like dabbling in thoughts and ideas. Do you like reading?” he asked.

“Yes, I like it, especially in the evening. It helps me fall asleep. Unless I’ve drunk too much, like last night, and can’t see straight”.

“So you admit that you were drunk yesterday”.

“I have no reason to deny it”.

“That would explain your behaviour then”.

“What do you mean?”

“I did tell you that that woman is not for the likes of you and me!”

“Martha?”

“What Martha? I’m talking about Rosemary. Be careful if you don’t want to fall flat on your face”, he concluded and went on shaving with the dexterity of a violinist.

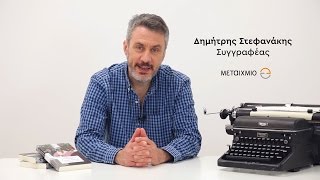

Dimitris Stefanakis - Translation: Irene-Noel Baker

Comments - Σχόλια